Today the focus

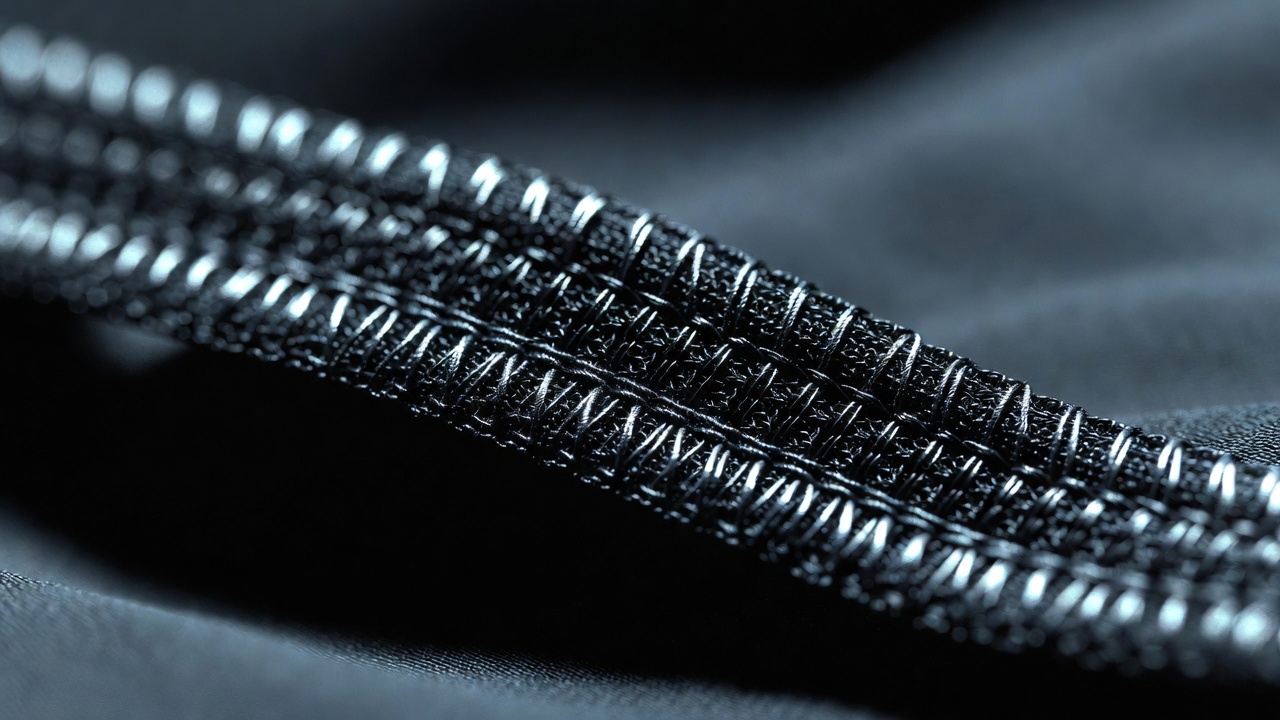

Why Rugby Jerseys Use Reinforced Stitching (And Why NFL Fans Care)

Explore the tech behind rugby jersey quality. Learn why reinforced stitching is essential for contact sports and why NFL jersey collectors are turning to rugby-grade durability.

What Does the "C" Mean on NFL Jerseys? Captain Symbols Explained

Ever wondered why some players have a "C" patch on their chest? Discover the meaning behind the NFL captain's patch, the gold star system, and why some teams choose not to wear them.

Why Every Fan Needs a Vintage NFL Jersey in Their Collection

Explore the world of vintage nfl jerseys. Learn why old nfl jerseys are more than just sports gear—they are fashion statements and valuable investments for every football fan.

Reebok vs. Nike NFL Jerseys: A History of Quality and Style

Comparing the two giants of NFL apparel. We analyze the fit, durability, and fabric of nfl reebok jerseys vs modern nike kits. Find out why collectors still hunt for classic Reebok gear.

How to Order Custom NFL Football Jerseys for Your Team: A Pro Guide

Looking to outfit your flag football or amateur team? Learn how to order custom nfl football jerseys, choose the best fabrics, and find a reliable custom nfl jersey store.

How to Remove Stains from a White NFL Jersey: Professional Tips

Keep your "Away" kits sparkling! Learn professional secrets to removing grass, mud, and food stains from a white NFL jersey without damaging the fabric or logos.

NFL Jersey Size 48 and 52 Explained: What Numerical Sizing Means

Confused by numerical jersey sizes? Our guide explains what NFL jersey size 40, 44, 48, and 52 mean in inches and how they compare to standard S, M, L, and XL fits.

Identifying Authentic NFL Jersey Tags: A Collector's Guide to Authentication

Don't be fooled by fakes! Learn how to read authentic nfl jersey tags, identify real holograms, and master jersey authentication with our expert guide.

What is an NFL Elite Jersey? Is the $350+ Investment Worth It?

Deep dive into the Nike NFL Elite Jersey. We analyze the Vapor F.U.S.E. tech, numerical sizing, and professional stitching to see if the world's most expensive football jersey is worth the price.

Women’s NFL Jersey Sizing Guide: Fit, Styles, and Fashion Tips

Unsure about women's nfl jersey sizing? Our guide explains the difference between Game, Limited, and Legend fits for female fans, plus tips on how to style your jersey.

Reebok vs. Nike NFL Jerseys: A History of Quality and Style

Comparing the two giants of NFL apparel. We analyze the fit, durability, and fabric of nfl reebok jerseys vs modern nike kits. Find out why collectors still hunt for classic Reebok gear.

NFL Jersey Size 48 and 52 Explained: What Numerical Sizing Means

Confused by numerical jersey sizes? Our guide explains what NFL jersey size 40, 44, 48, and 52 mean in inches and how they compare to standard S, M, L, and XL fits.

Identifying Authentic NFL Jersey Tags: A Collector's Guide to Authentication

Don't be fooled by fakes! Learn how to read authentic nfl jersey tags, identify real holograms, and master jersey authentication with our expert guide.

What is an NFL Elite Jersey? Is the $350+ Investment Worth It?

Deep dive into the Nike NFL Elite Jersey. We analyze the Vapor F.U.S.E. tech, numerical sizing, and professional stitching to see if the world's most expensive football jersey is worth the price.

Women’s NFL Jersey Sizing Guide: Fit, Styles, and Fashion Tips

Unsure about women's nfl jersey sizing? Our guide explains the difference between Game, Limited, and Legend fits for female fans, plus tips on how to style your jersey.

Youth NFL Jersey Size Chart: A Complete Buying Guide for Parents

Shopping for a young fan? Our NFL youth jersey size chart and buying guide help you find the perfect fit for kids of all ages. Learn about sizing hacks and growth tips.

Real vs. Fake NFL Jersey: 7 Ways to Spot a Counterfeit in 2024

Don't get scammed! Our expert guide shows you exactly how to spot a fake nfl jersey vs a real one. Check stitching, holograms, and tags like a pro collector.

Do NFL Jerseys Run Big or Small? A Detailed Brand & Tier Comparison

Unsure which size to order? We answer the burning question "do NFL jerseys run big" by comparing Nike Game, Limited, Elite, and Mitchell & Ness throwbacks. Find your perfect fit here.

Stitched vs. Screen Printed: Why Stitched NFL Jerseys are the Better Investment

Choosing between a Nike Game and a Limited jersey? Our guide compares stitched vs. screen-printed NFL jerseys, covering durability, comfort, and value for collectors.

Ultimate NFL Jersey Size Guide: Find Your Perfect Fit for the 2024-2025 Season

The ultimate NFL jersey size guide for 2024. Compare Nike Elite, Limited, and Game jerseys. Learn how to measure and find the perfect fit for your next jersey purchase.

How to Remove Stains from a White NFL Jersey: Professional Tips

Keep your "Away" kits sparkling! Learn professional secrets to removing grass, mud, and food stains from a white NFL jersey without damaging the fabric or logos.

How to Dry a Football Jersey Without Ruining the Print: The 3 Golden Rules

Don't put that jersey in the dryer! Learn the professional secrets to drying football jerseys, protecting the print, and preventing fabric shrinkage. Essential jersey care for every fan.

How to Wash NFL Jersey: 5 Expert Tips to Keep It Like New

Don't ruin your expensive football gear! Learn the professional way to wash NFL jerseys, protect stitched numbers, and prevent fading with our step-by-step guide.

What Does the "C" Mean on NFL Jerseys? Captain Symbols Explained

Ever wondered why some players have a "C" patch on their chest? Discover the meaning behind the NFL captain's patch, the gold star system, and why some teams choose not to wear them.

Why Every Fan Needs a Vintage NFL Jersey in Their Collection

Explore the world of vintage nfl jerseys. Learn why old nfl jerseys are more than just sports gear—they are fashion statements and valuable investments for every football fan.

How to Order Custom NFL Football Jerseys for Your Team: A Pro Guide

Looking to outfit your flag football or amateur team? Learn how to order custom nfl football jerseys, choose the best fabrics, and find a reliable custom nfl jersey store.

How to Create Your Own Custom NFL Football Jersey: A Step-by-Step Guide

Want a unique look? Our guide to custom nfl football jerseys covers everything from personalizing your favorite player's kit to designing full team uniforms. Stand out on game day!

10 Most Iconic Retro NFL Jerseys of All Time: A Collector’s Guide

Relive the glory days! We rank the top 10 most iconic retro nfl jerseys every fan needs, from Joe Montana to Bo Jackson. Discover why vintage kits are the ultimate style statement.

Why Rugby Jerseys Use Reinforced Stitching (And Why NFL Fans Care)

Explore the tech behind rugby jersey quality. Learn why reinforced stitching is essential for contact sports and why NFL jersey collectors are turning to rugby-grade durability.

NFL vs. Rugby Jersey: What are the 5 Main Differences?

Ever wondered why rugby and NFL kits look so different? We compare nfl vs rugby jersey design, durability, and fabric technology. Discover which is the tougher sports gear.